Over the course of November 26-30, the GOP and Democratic caucuses in the Georgia Legislature have released their legislative map proposals.

Senate

- Senate has 56 total seats, majority is 29.

- The GOP’s proposed Senate map keeps the party composition at 33R-23D by packing two majority-black districts and eliminating two majority-white Democratic districts.

- The Democratic response would shift the party composition to 31R-25D by adding two majority-Black districts in the southern Atlanta suburbs.

- The Democrats are challenging the GOP Senate map as not fulfilling the court order. Won’t be surprised if it goes back to court.

- Looking at the glass half-full, the current Senate party composition is the closest its ever been since Republicans gained the Senate majority in 2003-2004 for the first time since Reconstruction. They held it at 30R-26D, then increased it to a historic 39R-17D by 2016 before Democrats began bouncing back from 2017 onward.

- More analysis by Niles Francis.

House

- House has 180 total seats, majority is 91.

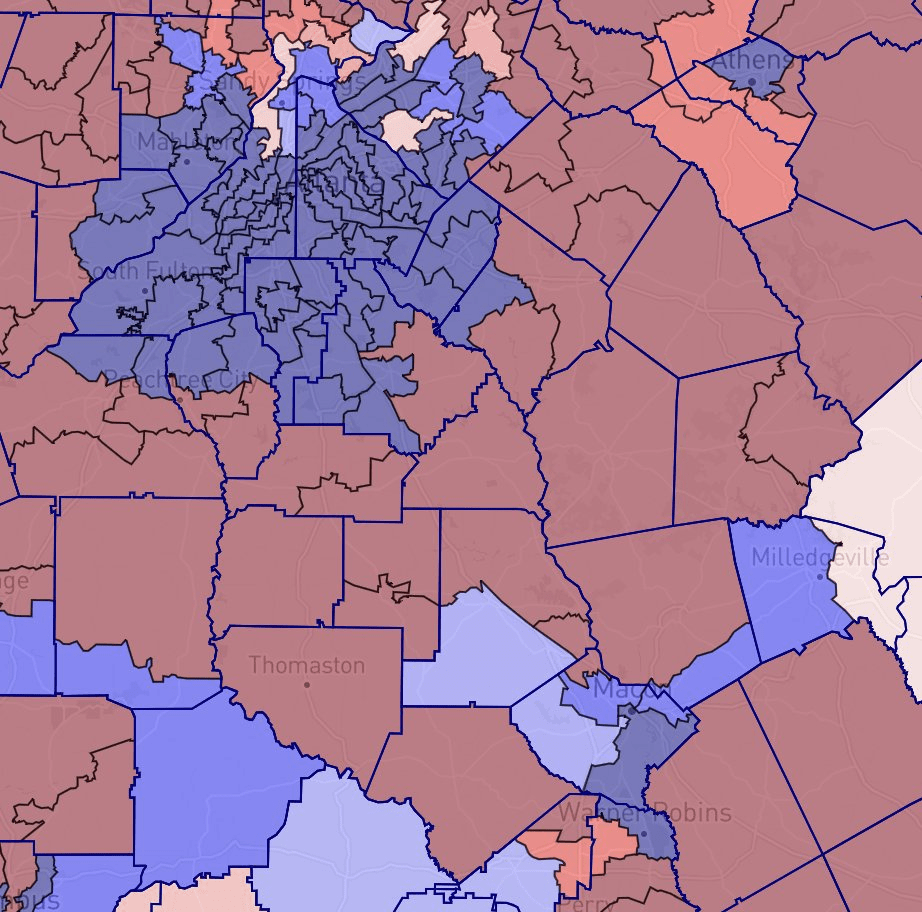

- The GOP’s proposed House map brings the party composition of the House in 2025 to 99R-81D, down from the current composition of 102R-78D.

- The Democratic response would modestly bring the party composition to 96R-84D by creating four majority-Black and one plurality-Black districts while double-bunking or flipping some Republican seats in the process.

- Not as much Democratic outcry about the GOP House map as there is against their Senate map. However, there is disagreement from expert testimony on whether the House map passes the VRA smell test.

- The last time the GOP was under 100 members in the House was the 148th General Assembly in 2005-2006, when the GOP held the House for the first time since Reconstruction. It was 99R-80D-1 independent. From there, Republicans ascended to a high of 119R-60D-1 independent 2013-2016 before Democrats bounced back from 2017 onward.

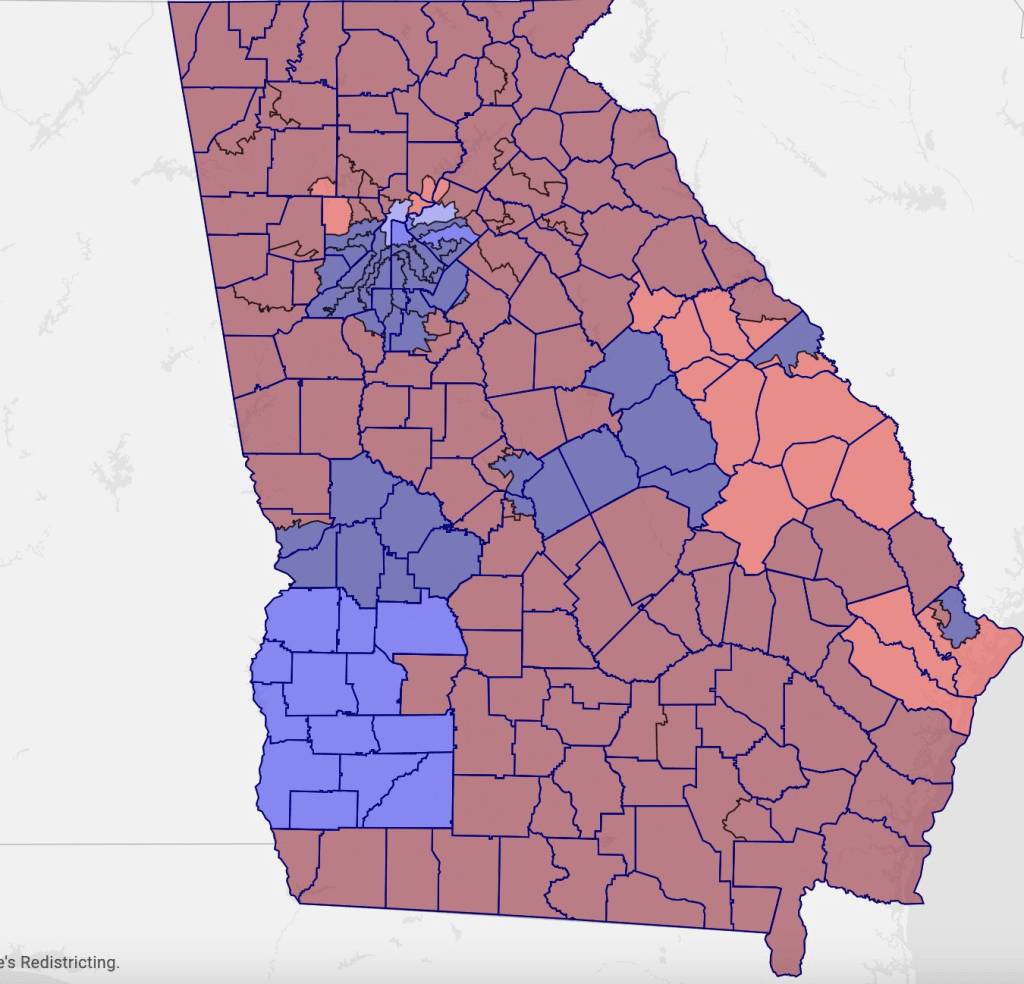

- Under both House maps, Houston County finally gets Democratic House representation, with the map stretching HD143 (currently held by House leader James Beverly) to represent Warner Robins and northern Houston County while splitting central Macon into three blue districts stretching into surrounding counties.

- Larry Walker was the last Democrat to represent a portion of Houston County in the House, way back in the 147th General Assembly (2003-2004).

- Nothing in Greater Columbus was touched (obviously).

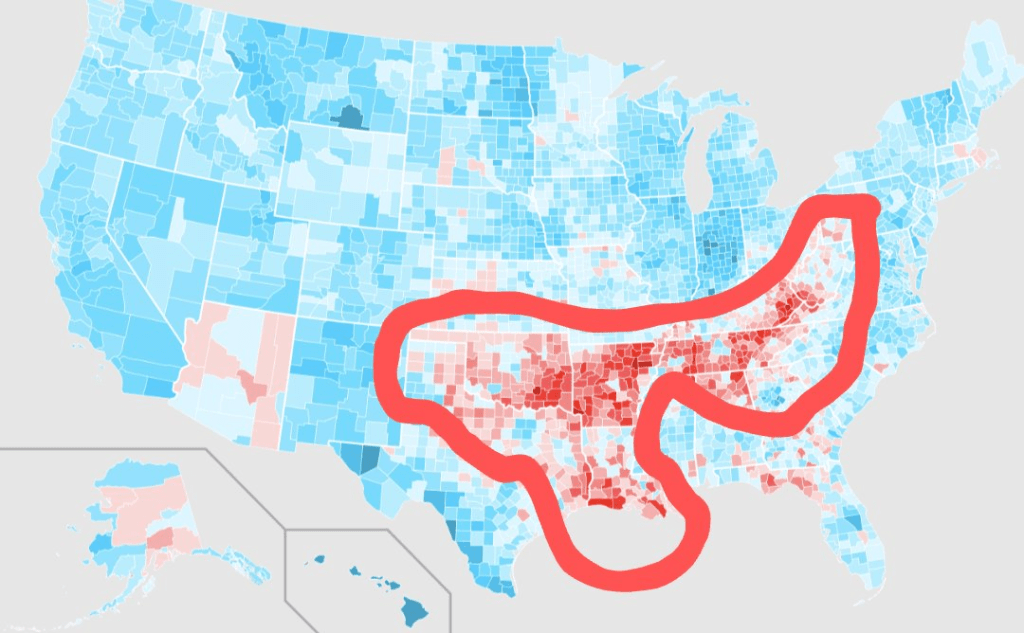

- The map definitely strengthens the Black Belt’s African American representation a bit.

- This map, and the Democratic response, reflects how the state’s popular vote has shifted to the left in the last several elections.

- More analysis by Niles Francis.

Notes

- Even on gerrymandering grounds, I wonder why the GOP wants to keep the current margins for Senate while conceding 3 seats in the House. I’d have expected at least one concession in the Senate for a 32R-24D map.

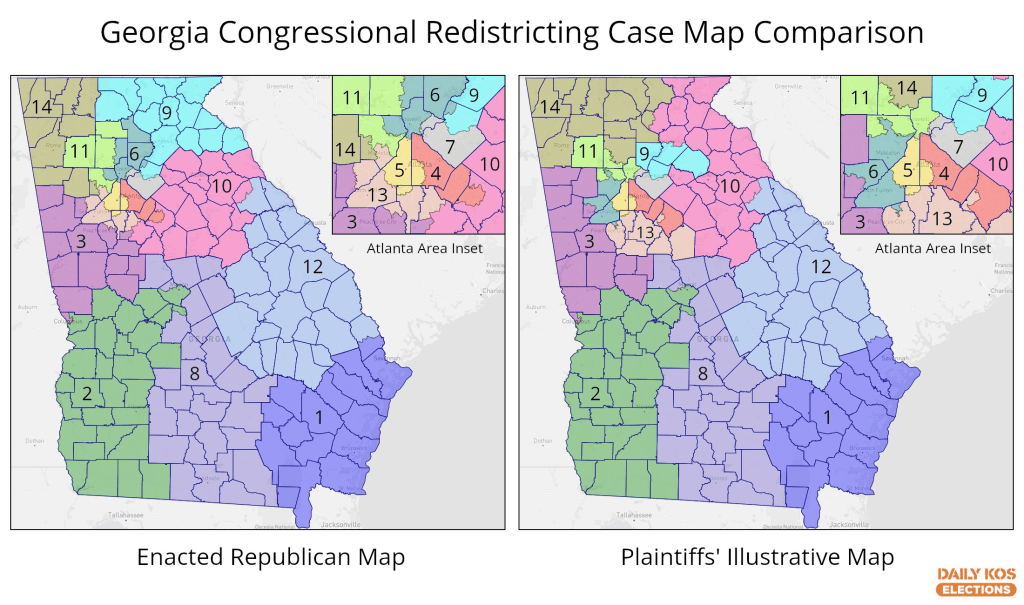

- I wouldn’t be surprised if, in the congressional map phase, the GOP goes the route of packing more Black voters into Lucy McBath’s GA07 rather than redraw the west Atlanta suburbs between the 3rd, 6th, 11th, 13th and 14th districts. The Dems are hoping to keep the 7th intact.

Democrats are hoping for something like this (courtesy Stephen Wolf @PoliticsWolf):