Reading Josh Marshall’s recent post positing a theory of “civic sede vacantism“, which posits that American liberals/progressives need to narratively and linguistically treat the current regime – both in the executive and the judicial branches – is operating so much outside of the constitution that it cannot be expected to curtail or regulate its own abuse of power, and that it is up to libprogs to use state power to curtail federal power and restore constitutional government.

I find the idea interesting in how it comes around to effectively calling for progressive federalism in deed, but doing so from the position of reacting to a “fallen” political order which ought to be rejected in its legitimacy, curtailed from its uses of power, and corrected into a better relationship with its power.

You can find this sort of legitimism/sedevacantism in a number of cases:

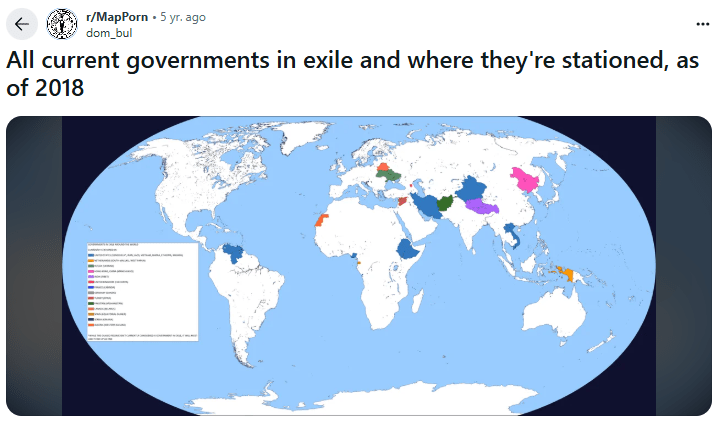

- Anyone who has ever maintained a government-in-exile after fleeing a country (i.e., the Second Spanish Republic government in exile from 1939 to 1977) or have maintained claims to a former monarchy;

- Catholic sedevacantism, in which some Catholics reject the legitimacy of any pope since Pius XII due to the holding of the Second Vatican Council, and may instead elect antipopes with rival claims to the Roman papacy;

- Irish republican legitimism, which posits that the pre-partition all-island Irish Republic declared in 1919 is still in existence and rejects both the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty and the existence of the modern Republic of Ireland;

- Sovereign citizens who believe that the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution converted “sovereign citizens” into “federal citizens” by their agreement to a contract to accept benefits from the federal government, and that the United States stopped being a legitimate country afterward, instead becoming a “corporation” (the SovCit who originated this, of course, was a white supremacist);

- Sovereign citizens in Europe (Russia, where some believe that the USSR continues; the Reichsburger movement in Austria and Germany; some in the Czech Republic who believe that the dissolution of Czechoslovakia was illegal, etc)

This can easily go down the road of conspiracy theory mongering, but I can respect the cognitive dedication to an alternate, rival status quo.

But if we’re departing from the status quo narrative, why start with Trump 2? Why even start with George W. Bush’s 2000 “election”?

Equal Rights Amendment

In fact, let’s date it to the moment when Congress erroneously inserted a ratification deadline to the Equal Rights Amendment.

Was it Congress’s authority to impose a statutory deadline on ratification? It’s debatable. Who’s idea was it to add a deadline? These questions have been brought up repeatedly in court.

One can argue that Congress abrogated its legitimacy as a branch of government by interfering with the ratification of a constitutional amendment after its legitimate proposal.

POTUS (Nixon and Carter) and SCOTUS also signed off on this deadline, so they get the chop too.

It’s also how this imposition of an illegitimate deadline, not only for the ERA (1979, then 1982) but also for the DC Voting Rights Amendment (1985), resulted in no further amendments being proposed by Congress after 1978 to this day.

This was supremely violative of the amendment process. It arbitrarily suppressed the relationship of the states with the constitution. It was the moment when the broader Second Reconstruction era ended as a constitutional movement and began to slowly recede, especially after William Rehnquist became Chief Justice in 1986 and John Roberts in 2005.

This abdication of legislative responsibility led to SCOTUS intervening for the right to abortion in Roe v. Wade (1973-2022) and subsequent progressive readings of 14th Amendment jurisprudence, all of which are now vulnerable to retirement. All of that should have been Congress’s responsibility to propose, and for the states to ratify at their pleasure.

So if the White House is constitutionally vacant, so is Congress and SCOTUS, all since 1972.

Civic, constitutional sedevacantism (legitimism?) should apply to all three branches and their actions since 1972, regardless of party or impact. I think that’s a good rupture point.

But what would this mean in practice?

A Progressive, Provisional Congress-in-exile

I’d argue that a sedevacantist position would take the following stances:

- The Equal Rights Amendment was fully ratified by Virginia on January 15, 2020, and is therefore of legal effect nationwide.

- The entire federal government since 1972, including all federal government elections and terms of Congress, all nine presidents (from Ford to Trump), all SCOTUS terms, and every statute, executive proclamation and federal judicial ruling, is illegitimate.

- Yes, even the good laws and decisions, like Roe v Wade, Lawrence v Texas, Obergefell v Hodges, Bostock v. Clayton.

- The D.C. Voting Rights Amendment, proposed by an illegitimate Congress, was also improperly abrogated by a seven-year deadline.

- The pragmatic approach would be to engage with the illegitimate federal government, but with a political imagination as to blotting out the legitimacy of every action taken by the federal government against the Second Reconstruction agenda.

- The more idealistic-but-isolative approach would be to establish a United States government-in-exile:

- complete with all three branches of government

- electing a Provisional president and provisional Congress

- appointing a provisional Supreme Court

- loyal to the Constitution as amended by January 15, 2020

- recognizing the D.C. Voting Rights Amendment as still open to ratification by the states, and the statutory deadline of 1985 as invalid

- open to proposing further amendments by two-thirds of the Provisional Congress

- selectively supportive of certain statutes passed since 1972

- diverging from the illegitimate federal government in foreign policy.

And how far could we go with the government-in-exile concept?

(Sidenote: What about state governments? I’d argue that the end of the First Reconstruction era in the South happened through illegitimate means at the state level, such as the forced resignation of Rufus Bullock, the liberal Republican governor of Georgia from 1868 to 1871, when he fled the state under threat from the Klan, which was followed by the significant, forced decline of equality under the law in Georgia. Or how Reconstruction was ended through bloodshed by the Klan. But that is for another post.)

Statutes under a government-in-exile would include most of what was unsuccessfully brought to the 111th and 117th Congresses (the two most recent Democratic trifectas):

- For the People Act

- Equality Act

- American Dream and Promise Act

- Paycheck Fairness Act

- Washington D.C. Admission Act

- Federal Death Penalty Abolition Act

- Sabika Sheikh Firearm Licensing and Registration Act

- Raise the Wage Act

- Family and Medical Insurance Leave (FAMILY) Act

- Trumka Protecting the Right to Organize Act

- FAIR Act

- U.S. Citizenship Act (including the NO-BAN Act)

- Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act

- George Floyd Justice in Policing Act

- Puerto Rico Admission Act

- Farm Workforce Modernization Act

- Eliminating a Quantifiably Unjust Application of the Law (EQUAL) Act

- Assault Weapons Ban Act

- Ensuring Lasting Smiles Act

- SAFE Banking Act

- CROWN Act

- Recovering America’s Wildlife Act

- Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act

- Augmenting Compatibility and Competition by Enabling Service Switching (ACCESS) Act

- Local Journalism Sustainability Act

- Averting Loss of Life and Injury by Expediting SIVs (ALLIES) Act

- American Innovation and Choice Online (AICO) Act

- Women’s Health Protection Act

- Democracy Is Strengthened by Casting Light on Spending in Elections (DISCLOSE) Act

- Fair Representation Act

But then I’d argue that even the most recent Democratic trifecta was playing it safe with the legislation it introduced. A Congress-in-exile would introduce bills to reform the federal government itself by statute, such as:

- expanding the Supreme Court to 25+ seats

- creating division benches of the Supreme Court, including a Constitutional Bench with exclusive right to interpret the constitution

- expanding the size of the House of Representatives

- allowing territories full voting rights in the House

- abolish the filibuster

- allow for shadow House delegates from federally-recognized tribal nations (including the Cherokee Nation and United Keetowah Band)

- extend House delegates terms to four years, same as that of Puerto Rico’s resident commissioner

- allow for territories to send nonvoting delegates to the Senate (a bill to this effect was introduced in 2019 by Delegate Michael San Nicolas of Guam)

- create the office of non-voting delegate to the Senate, to which all states elect four and all territories elect six

Finally, this Congress-in-exile can vote to approve by two-thirds for multiple, much-delayed proposals to amend the Constitution, sending them to the active state legislatures.

Conclusion

This is ultimately about changing the narrative about the federal government, away from a do-nothing entity encumbered by an ineffective Constitution, to one in which Congress fills in the gaps.

If it takes having to establish an alternative to this illegitimate status quo regime from abroad, so be it. If this is what it takes to repair the relationship between the United States and the world, so be it.

The deep wound inflicted by a wayward Congress against the Constitution since 1972 through a ratification deadline clause has to be resolved, even if by a Congress in exile.